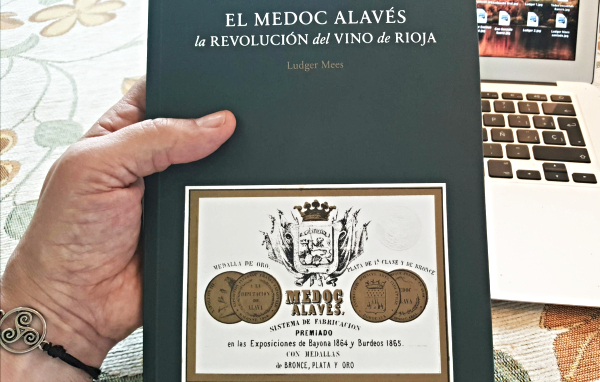

In his book, “El Medoc Alavés, la REVOLUCIÓN del VINO de RIOJA” [Alavese Médoc: The Revolution of Rioja’s Wine], Ludger Mees, history professor at the University of the Basque Country (UPV-EHU), asks himself and us:

What might be “the lessons that the past offers us?” In so doing, he links that Alavese Médoc experiment of 150 years ago to the wines of today and the future.

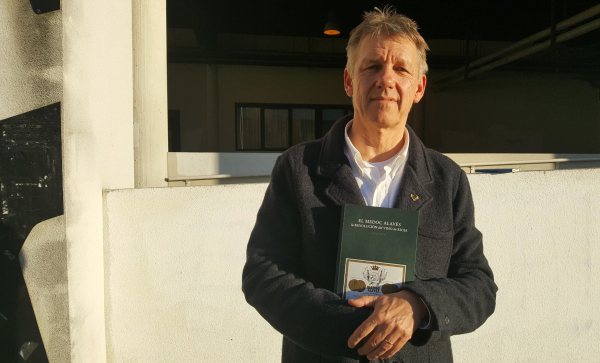

LUDGER Mees, Professor of History at the UPV-EHU.

What the professor and author believes clearly, quite clearly, is that…

“Twenty-first century Rioja Alavesa comes from the nineteenth century.”

Better late than never. We’ve been awaiting this conversation with the professor about his book, “El Medoc Alavés, la REVOLUCIÓN del VINO de RIOJA”. For my part, I read the book in June, one week before it was presented to the public. The book is magnificent. Ludger has studied and loves the Rioja Alavesa. He also drinks its wines. Even his sons understand that it is a treat to visit the region for an extended weekend.

Could there be anymore reasons to get down to work?

THE BOOK, basis of our conversation.

Julio Flor / Editor of the Blog Rioja Alavesa.(*)

Ludger Mees presented his book –fruit of more than a year-long investigation- last June 28 at the Lanzaga bodega in Lantziego along with its publishers, Telmo Rodríguez and Pablo Eguzkiza. The Minister of Culture for the Basque Government, Bingen Zupiria, and the President of the Regional Council of Álava, Ramiro González, also in attendance, committed themselves to the collective effort to produce wines of character, quality, and distinction.

Mees’s book recounts the history that took place in the Rioja Alavesa over 150 years ago, when the region produced a wine that could not be transported or resist the summer’s high temperatures. In response, the Regional Council at that time, along with several distinguished figures and some ten municipalities, joined with winemakers in an endeavor to create a quality wine which could travel and survive the summer heat.

HARVEST baskets from those vintages… (an image from the book).

The new wine’s first harvest arrived in 1862, aged in oak barrels.

“A commission was formed that employed a rigorous labeling process to determine who did and did not meet quality control standards. In addition, an extensive marketing campaign was carried out that was felt as far as the Royal Palace in Madrid. And wine from the Alavese Médoc was given to pharmacists, journalists, and diplomats.”

The venture lasted between 1862 and 1868, winning international awards at the expositions of Bayonne in 1864 and Bordeaux in 1865, including Bronze, Silver, and Gold medals.

ANOTHER photograph from the book, depicting an old harvest.

“This book is a tribute to great and small protagonists. I have the privilege to speak today with the inheritors of that fascinating experiment of the Alavese Médoc. I have you in front of me!” he said then –at the presentation of the book- referring to and mentioning the “representative institutions, vintners, harvesters, viticulturists, and lovers of good wine…Because the Alavese Médoc was not the product of an isolated individual, but rather of a collective effort.”

That Thursday, June 28, the book’s author read an excerpt from a poem written by his compatriot, the German poet Bertolt Brecht, entitled “Questions of a Worker Who Reads:”

The writer presented the book in June, very near to the ilexes that surround the Lanzaga bodega.

Young Alexander conquered India. / Was he alone? / Caesar defeated the Gauls. / Did he not have so much as a cook with him? / Philip of Spain wept when his armada / Went down. Did no one else weep? / Frederick the Second was victorious in the Seven Years’ War. / Who else prevailed? / On every page a victory. / Who cooked the victory banquet?

“You can almost go to the Rioja Alavesa with your eyes closed in search of a good wine and hit the mark“

.- When you presented your book, “El Medoc Alavés, la REVOLUCIÓN del VINO de RIOJA”, you stressed the collective project of those that made it possible with that poem.

It is one of the principal theses: that all this would never have succeeded if it had been the initiative of just one person or one institution.

THE interview took place on January 15 in his office at the UPV-EHU in Leioa.

.- There were a lot of people involved.

A great variety of people participated in the Alavese Médoc. Enlightened aristocratswith relations beyond the frontier and open mentalities. Well-connected politicianswho were also capable of looking beyond the day-to-day. Then there were the first specialists, well-trained in France, the Mecca of good wine. And there were a number of important harvesters, whose names sometimes appear in the documents and sometimes do not.

.- Among all those names, was there someone in particular who catches your attention, who had the most impact on the Alavese Médoc project?

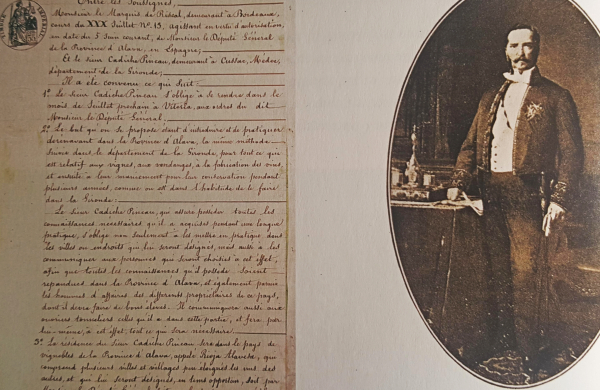

It is difficult to cite just one because the contribution of each and every individual was very important. Begin with Jean Pineau, who brought with him all the secrets of the elaboration of wine. But then consider the silent labor, so important, of Pineau’s translator, because someone had to translate. And Eugenio Garagarza, a man who experiences the project as the director of Álava’s model farm.

JEAN Pineau, one of the book’s protagonists, is buried in Elciego.

Or the Marquesses of Riscal, who were two, the father, Guillermo, with his professional contacts in Bordeaux, and later the son Camilo, who takes the reins and creates a bridge between Médoc and Álava. And without doubt,Pedro Egaña, that man so important in the history of the Basque Country, since he was the first to talk of a Basque nationality in his famous speech in the senate, not long before becoming President of Álava’s Regional Council.

.- One notes that the writer is a historian. You title chapter 8, “Recount the past, discover the future.”

I’m an old-school historian who thinks that although history never repeats itself, we can draw conclusions. It is the only tool, the only indications that we have to orient ourselves a bit in the present. From that perspective, you realize that many of the basic problems, despite all the changes that have occurred, continue repeating today.

“RECOUNT the past, discover the future”… It is evident that the writer is a professor of history.

.- For example.

How we recover from a crisis. When in general in Europe the first response is to cut public funding… In Spain they have cut funds for research knowing full well that innovation, investigation, is what will help us get out of the crisis.

That is what was done with this experiment that was born in the context of a tremendous social crisis in the Rioja, which affected thousands and thousands of families, an entire important sector of the population. The usual remedies were not sufficient to recover; instead new solutions, approaches, etc. were necessary.

.- If we had the method, if international awards were won with the Alaves Médoc, if we were proud of this wine… Why did it last only six years? Why did it not continue?

THE AUTHOR of “Medoc Alavés, la Revolución del Vino de Rioja” with the book in his hands.

I see you have read the book well, because the Alavese Médoc disappeared in 1868. There are several reasons. One, it was an experiment that was before its time. Moreover, it could have only worked if there had been people who could allow themselves the luxury to store wine for three years without selling it. At that time, the industrialization of the Basque Country had not yet begun. French capital, which would come later, had also not yet arrived.

Additionally, 1868 was the year of the Revolution in Spain, dubbed as Glorious, a time of profound changes.

.- You have said twice that the Alavese Médoc was “an experiment.” Was it something more than an experiment?

It was an experiment that ultimately worked out and produced a result. A new wine, as well as that whole publicity campaign that took place at the time. We are talking about the sixties in the nineteenth century, launching a tremendous marketing campaign. They also created a label for the new wine, which managed to fetch very attractive prices where it was sold.

TREATING barrels with sulfur, another photograph from the book.

.- An experiment that was on stand by for some time.

Yes, because when industrialization arrives in the Basque Country, and Basque capital begins to enter into the Rioja along with the railroad, on the other side of the Ebro, in Haro and the like, that is when they can take advantage of the work that was already done, and of the label’s prestige that already existed, solving the problems of distribution.

.- Pineau remained in Elciego for a few decades, where he is buried, and one of his sons founded the cooperage, the barrels in Laguardia…

Riscal made use of that because Álava’s Regional Council experienced a political crisis during those years anddecidedthere no longer was money to extend Pineau’s contract.

MARQUÉS de Riscal, one of the Rioja’s oldest bodegas. Founded in 1858.

.- Twenty-four years ago the Regional Council published your first book about the Alavese Médoc. How much enthusiasm did you see in Rioja Alavesa?

At the time I was involved in a larger research project about the process of modernization in the Alto Ebro and Catalonia, financed by the Volkswagen Foundation, which liberated me from three years of teaching. The Regional Council of Álava knew of the project, and I wrote a couple of brief articles in the press after learning about the subject. That is when I met Jaime, Telmo Rodríguez’s father. This was the background when the Regional Council asked me to write the short book.

It must be said that that book has nothing to do with this one. Today I can say: in that other book there are a few errors. It was the product of a larger investigation that had another objective, which came together in a book that we published in German.

In the new book, however, there is just over a year of long research invested, in which I have also relied on an assistant in the archives. The errors of the first book have been corrected in this one.

THE Regional Council’s President and the Minister of Culture for the Basque Government attended the book’s presentation.

.- From the Regional Council’s perspective, was there an eagerness to discover more about what differentiates our wines, our history, and the Rioja Alavesa twenty-four years ago?

The very factthat the Regional Council would decide, upon learning about that history…-I found the label, quite beautiful, of the first Alavese Médoc- to publish that short book, as rudimentary as it was, demonstrates that they were interested to know more and to impart it.

.- On the day of the book’s presentation in Lantziego, the current President of the Regional Council, Ramiro González, said that the book “is a history of visionaries.” Do you agree?

The difference between a businessman who thinks about the day to day, or tomorrow’s markets, and those people in the nineteenth century is notable. That is why I speak of an “experiment,” because you never know how an experiment will work out. To believe something interesting might result from this, you must possess a vision that goes beyond the day to day, or the next elections, beyond short-term economic or political benefits.

TELMO Rodríguez, Bingen Zupiria, Ludger Mees and Eduardo Aguinaco last June 28.

.- On the day of the book’s presentation you were surrounded not only by Telmo Rodríguez and Pablo Eguzkiza, but also the Basque Minister of Culture and the President of Álava’s Regional Council. Do you think today’s Regional Council, that our politicians, possess that vision?

I was pleasantly surprised by their speeches, both that by the Basque Minister of Culture, Bingen Zupiria, as well as the speech by the President of the Regional Council, Ramiro González, becauseI had the impression that they meant what they said, that they were not the typical speeches that someone has written for you. What’s more, Ramiro González, for obvious reasons, is more familiar with these issues. Plus, both had read the book!

.- Of course.

You say “of course,” but that is very important. I’ve seen many book presentations where that does not happen. Where they take out a piece of paper and read what the advisor has written.

.- It’s a great book, Ludger. One of the best that I have read about the Rioja Alavesa.

STAIRS in the Division of Social Sciences and Communication at the UPV-EHU.

Well, I will tell you that, despite being written only in Spanish, this book is better known abroad –I have given various talks in Europe, in Florence or in London- where I have many colleagues who know that I have spent more than a year working on this. They all ask me, “when will there be a translation of the book, published in English?”

I informed the Regional Council’s President about this issue, to whom the book’s publisher, Telmo Rodríguez, has offered the possibility of an English edition. And if it is wished, in Basque as well. An English version of this book would be quite important, since Álava’s wine could score lots of points among the international wine-literate public.

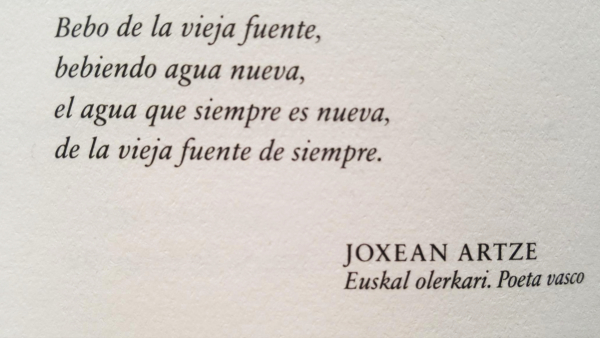

.- A verse by Joxean Artze appears at the beginning of the book: “I drink from the old fountain / drinking new water, / the water that is always new, / from the old fountain of always.” Can this be a way to understand the Alavese Médoc?

THE book opens with this verse by Artze chosen by the winemaker, Pablo Eguzkiza.

I think so. We can ask ourselves, how do we produce a quality product? To do that, one must look at what was done with the Alavese Médoc. At that moment, a quality product meant substantially reduced production that you can control, to ensure that it meets all of the criteria. A production very grounded in its soil. A wine that you can identify. That you knew came from Samaniego, or Laguardia, or Elciego… And it was not Riojan wine, but rather a micro wine where all the processes were controlled.

.- A wine with a DNI [National ID.], with a very concrete DNA for many years.

One knew from where it came, you knew the land, the climate, the geological conditions… And this has not changed. Today’s good wine, in a world of globalization, once more tends to that. We do not want a wine without a father or mother, no; what is appreciated are wines that you know where they come from and what you are drinking, wines that you know their history, philosophy, context, and what these people have taught us. Artze’s verse sums up this philosophy very well.

MEES, Zupiria, Telmo and Pablo listen to Ramiro González’s talk at Lanzaga.

.- On page 145 of the book you say: “Far from being a dead project and relegated to the dustbin of history, it is as current as ever.” You affirm this 157 years after the Alavese Médoc was put into motion.

There I’m trying to draw a comparison with that global context that appears to steer us ever closer to the homogenization of everything, of our lifestyles, etc. This is one side of the coin. The other is precisely that human beingsdo not like this, but rather to have their feet firmly on the ground. To know where we are, from where we came… and, in this sense, to know what we are drinking.

The great challenge for the future is to recover those essences, that spirit that permits us to live comfortably within the context of globalization.

“SEARCH for the authenticity of wine without makeup,” proposes Ludger Mees.

.- In the book you say that, “one must search for the authenticity of wine without makeup and of the landscape behind each wine,” referring to the soul of Rioja Alavesa’s viticulturists.

It’s a territory that isn’t mine, because I am neither an oenologist nor have sufficient knowledge to judge a wine from that point of view, but I can assess the Alavese Médoc’s project as a historian as well as a modern-day citizen. I have that impulse to blend those two perspectives. All kinds of judgments emerge from there that allow me to opine in that way, based on what I have studied.

.- Have we lost ourselves in globalization, in homogenization, or do we have a unique wine, and search for the flavors that peoples, lands, and vineyards give?

I don’t think that we have lost ourselves or found ourselves. We are in the thick of some very good conditions. One must realize that there are various factors implicated here. That question must be asked of those who make the wine, and those who consume it.

I would invite people to go to the bodegas that produce boutique wines, of limited production, cared for, with Alavese Médoc’s spirit, that show you how they are making it. This helps us realize that these bottles of wine cannot cost 4 Euros.

IN his office, this poster says: “He who does not wish to think will be expelled.”

.- Are we willing to pay more for such a wine, or do we continue to look for one that is “good and cheap?”

I am willing to pay more because I value that effort, that tradition, and the Médoc’s spirit. I can afford it to certain extent, although I still have two sons who are preparing their doctorates abroad.

…You asked me if we have lost.

I do not think that the Rioja Alavesa has lost due to globalization. We have our feet on the ground, with some optimal conditions to advance, but if we believe that we have already achieved everything, whether producers or consumers, that would mean resting on one’s laurels.

“IT’S going well, with its feet on the ground… but Rioja Alavesa should not rest on its laurels.”

.- To finish the book you say that “the key to good wine, yesterday, today, or tomorrow, is found in the fusion between the maximum loyalty to the local environment and the respect for its specific characteristics, on the one hand, and the search for innovative improvements on the other.” This is how the history professor concludes this good book.

Yes, yes. But to reach that point there are 154 pages of history. That is my opinion. That is why I say that we are well, but the journey continues, and there is room for improvement.

.- How do we convince the world about our great wines?

In that we still have a lot of room for improvement because our good wines from Rioja Alavesa exist abroad and, at the same time, are relatively unknown worldwide. I’ve brought friends and groups of foreigners (the last one included 20 Germans) to Laguardia and Elciego, where Paco Hurtado de Amezaga received us in Riscal, and we toured all the towns in a bus. I have told them the history, they tasted the wines, and they were enchanted, in love.

JEAN Pineau’s contract; and Pedro Egaña, President of Álava’s Regional Council at the time.

.- Where were their questions?

Everyone asked me, “how can we find out more about Rioja Alavesa?” How can they know more about the region if they ask in Germany, if they ask in England?How? It sounds bad that I say this as the author of the book, but Médoc’s history is so fascinating that if this book is published in English it will permit us to reach a greater public with a certain cultural level.

.- Do you think that the winds in 2019 are favorable to recover all that that occurred 157 years ago? Is it a good moment for the Rioja Alavesa and ‘the spirit of Médoc?’

The spirit of Alavese Médoc is catching on among many people. We are in a transitory phase in which we will decide where we wish to go. To that model; or to another older one, which is “good, pretty, and cheap” wine, but without soul.

“DOES or doesn’t the wine from Rioja Alavesa have soul?”, we asked the writer.

.- Is our wine, that from Rioja Alavesa, more of a wine with soul than without soul?

It is difficult to find a region in Europe or in the world with such a dense concentration of small wine makers that produce quality in general. And I would say that it is difficult to find a bad wine in Rioja Alavesa.

It sounds banal, but depending on where you go it’s not like this. Here, you can almost go to the Rioja Alavesa with your eyes closed in search of a good wine and hit the mark. This is unique with respect to other regions.

So, yes, our wines have soul.

AT our conversation at the UPV, we covered 150 years of Rioja Alavesa’s history.

.- We still want to know if today’s viticulturists might see themselves in the mirror of that Alavese Médoc, which was a collective project, and compare their image.

The contexts are very different. But if we are as we are, this does not come from a vacuum. What we are comes from all that, and from a long history. The twenty-first-century Rioja Alavesa comes, among others, from the nineteenth century. There is no other way to understand what there is here today.

AMONG the gathering, in June, there were many viticulturists from the region.

.- You had today’s viticulturists from Rioja Alavesa in front of you. And you talked to them.

That whole collective, inheritors of all that, who were in front of me, moved me. Because it is normal that a colleague of yours reads your book, but the person who holds the grapes and the bunches, who makes the wine, who handles vines more than book pages, went to my presentation having read my book.

“I read your book and it moved me,” they told me. For me that was a unique experience. Many told me that, and they asked me to sign the book, harvesters from small bodegas who had received the book from Telmo Rodríguez some time before.

Their eyes shone with delight.

For that reason I addressed them during the book’s presentation, giving an homage to all those people, the women as well, who do not appear in the documentary sources, but without which they would not have advanced in that time, the Alavese Médoc project and that revolution in Rioja’s wine would not have prospered.

(*)Translation: Aritz Farwell.

Suscríbete a nuestra Newsletter

Acepto que Blog Rioja Alavesa utilice mis datos para acciones de marketing

Recibe nuestras novedades

Newsletter

Acepto que Blog Rioja Alavesa utilice mis datos para acciones de marketing

Deja una respuesta